Remembering the Freedom of Choice

by Zoe Hanrahan

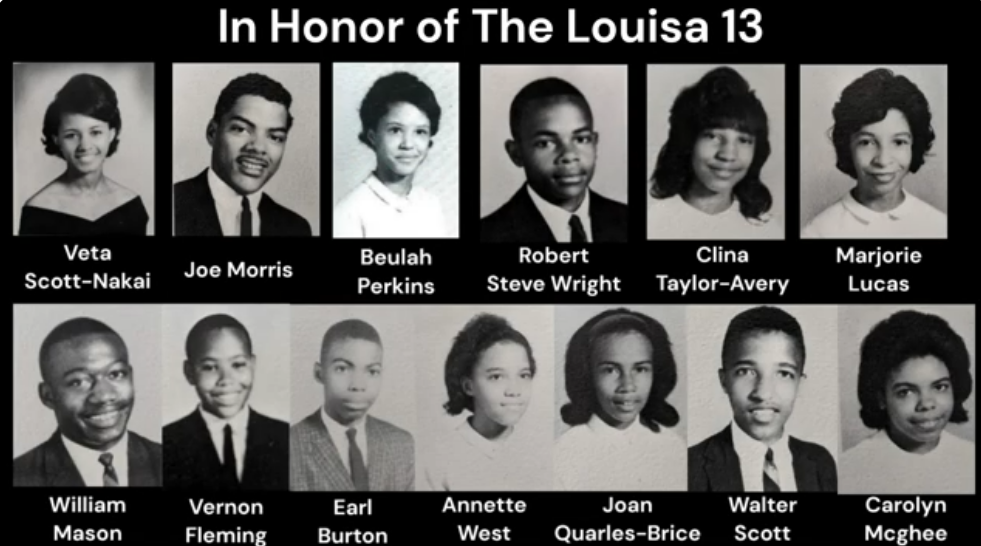

This photo submitted by Katelyn Coughlan shows seven of the students who integrated into Louisa County High School beneath the marker that commemorates them.

The idea for the Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project came to life when Vernon Fleming, vice president of the Louisa County Historical Society (LCHS), was having a weekly lunch date with one of his friends. Fleming was one of the first 13 students to enroll in Louisa County High School from the all-black A.G. Richardson High School in 1965 under the Freedom of Choice Plan.

He had not previously considered his experience one particularly worth noting. However, at his friend’s urging, he pitched the idea of exploring the topic to the rest of the LCHS. The group agreed to move forward, but with the added condition that since Fleming proposed the idea, he would be in charge of the project.

In 2021, under Fleming’s leadership, the LCHS began work on the Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project, gathering oral histories in the hopes of preserving the memories of both White and Black community members who had been students during the first year of integration at Louisa County High School. It was one of the first projects the historical society’s Community Advisory Council – whose purpose is to bring a more diverse perspective and help select the society’s African-American history projects – decided to be involved with.

“The project is important for two reasons. First and foremost, it’s recording a piece of history which has been long overlooked here in the county and putting a voice to the lived experience of the students who integrated the schools,” said Katelyn Coughlan, executive director of the LCHS. “Secondly, the name ‘Freedom of Choice’ is a misnomer because Black students were not afforded the same freedoms and choices as their White counterparts under this plan.”

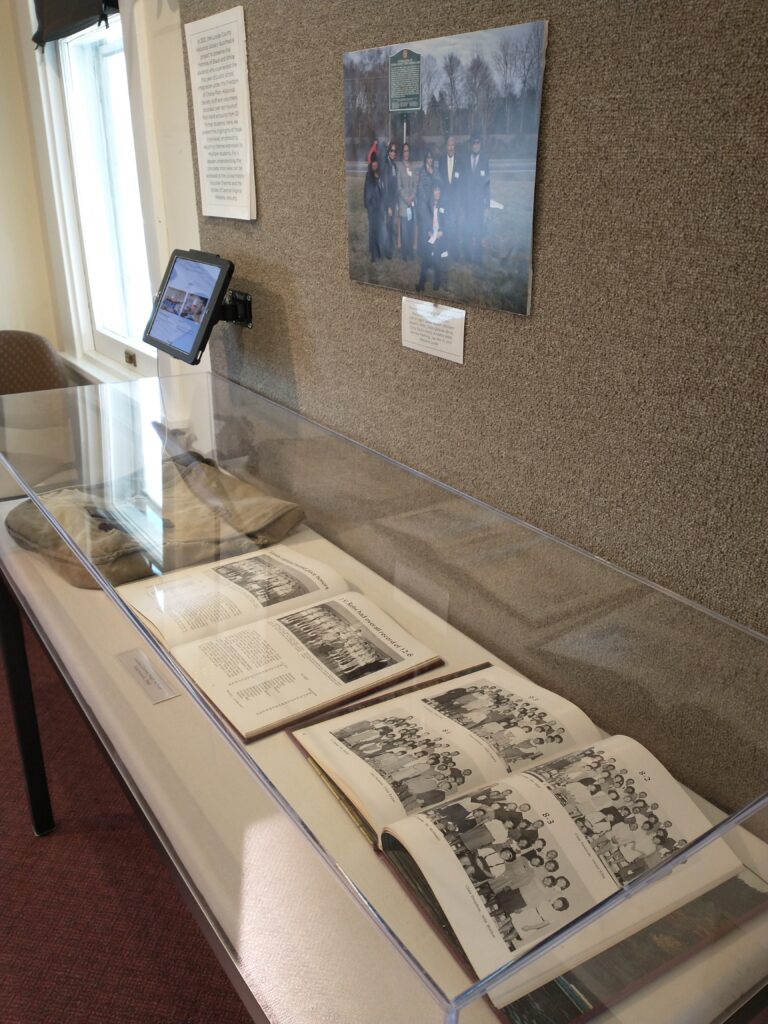

An exhibit at the Sargeant Museum of Louisa County History includes information gathered for the Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project (photo submitted by Katelyn Coughlan).

An exhibit at the Sargeant Museum of Louisa County History includes information gathered for the Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project (photo submitted by Katelyn Coughlan).

The Freedom of Choice Plan was put into effect in Louisa County eleven years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation unconstitutional in 1954. It followed efforts to maintain complete segregation, such as Senator Robert Byrd’s Massive Resistance movement.

In theory, the Freedom of Choice Plan allowed any student to choose the school they wanted to attend. In reality, it was used to avoid complete desegregation for as long as possible. Only 35 Black students, including the 13 at Louisa County High School, chose to integrate, and no White students chose to attend previously all-black schools. In fact, some White families chose to transfer their students out of the integrated schools, using state-provided vouchers to pay for all-white private schools. Black students did not have access to these vouchers or the private schools.

Efforts to craft the Freedom of Remembrance Project started during the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. The first steps of the project involved collecting stories from former students about their experiences with integration through a series of interviews. Fleming personally dedicated countless hours to both tracking down individuals willing to participate and conducting these interviews.

Clips of these interviews can be viewed on the LCHS website alongside a timeline displaying events starting with Brown v. Board of Education and ending with the integration of all Louisa County Public Schools. These clips can also be viewed on the LCHS YouTube channel. The full interviews, which range anywhere from 17 minutes to an hour, can be found on the Voices of Central Virginia’s website inside the Freedom of Choice Oral History Project collection.

The project, however, did not end after the interviews were wrapped up. Instead, the LCHS sought to expand the project by devoting their efforts to placing a historical marker commemorating the original 13 students who integrated into Louisa County High School. Placing the marker would turn out to be an endeavor that spanned 2021 and 2022 and was the first portion of the project that Coughlan herself worked on.

Fleming worked with county officials to gain approval to place the marker by Louisa County High School, but the group still needed to raise the funds required to undertake such an enterprise.

Louisa County Sheriff Donnie Lowe heard about the efforts to construct a marker, and when he learned the society needed to raise money to purchase and place it, he reached out to the president of the Louisa County Sheriff’s Office Foundation. The foundation decided to donate $1,500 for the monument, half of the total $3,000 needed.

The society met its fundraising goals, and on February 12, 2022, some of the Black students who chose to integrate in 1965 gathered – along with community members and leaders – to attend a dedication ceremony.

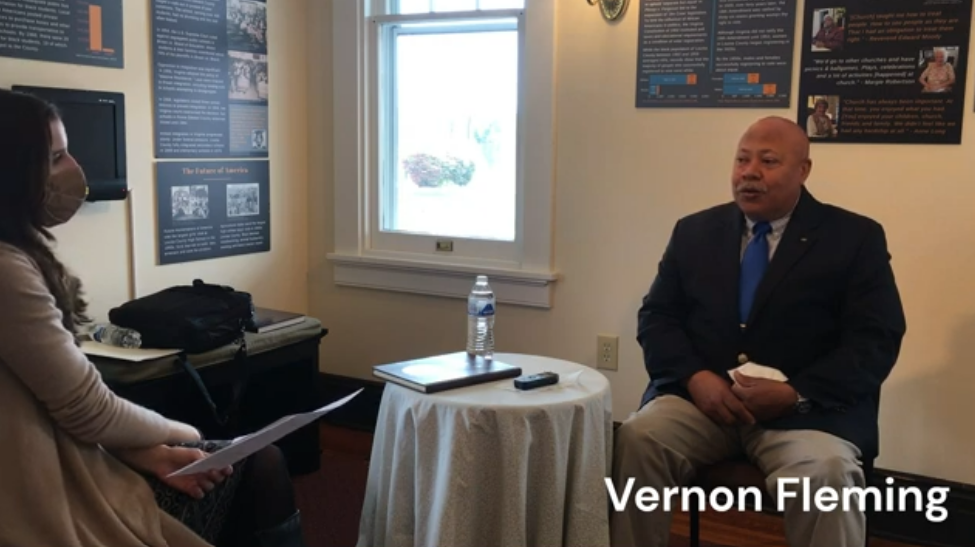

A screenshot from the Louisa County Historical Society’s “Feeling Invisible – Louisa County High School Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project” video.

Finally, in October 2023, the Sargeant Museum of Louisa History opened a new permanent exhibit showcasing information gathered from the interviews alongside material from secondary sources. The exhibit at the museum not only serves to display these valuable pieces of knowledge but also frames them within the context of the Massive Resistance movement. The museum welcomes guests to view the exhibit during its hours of operation, which are Monday through Friday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM. The project was not all smooth sailing, though, and there were a few obstacles the historical society had to overcome to bring the project to life.

“What I can tell you is that one of the largest hurdles we had to overcome was starting a project at the beginning of the pandemic,” Coughlan recalled. “Trying to conduct interviews remotely and in person with social distancing was really difficult.”

Outside of navigating the difficulties brought on by the pandemic, Fleming also faced the challenge of tracking down his fellow former classmates, some of whom he had not seen or heard from in the last fifty years. Even after Fleming managed to get into contact with them, some of the students who attended Louisa County High School during integration did not want to participate in the project.

“Some students, both Black and White, were reluctant to go on record because they were worried about how their families may have been impacted and how the oral histories would be used,” said Coughlan. Others had different reasons for being reluctant to recount their experiences with integration in Louisa County.

“Some felt it was dredging up old memories, and some, before we got to formal interviews, started to share a lot on phone calls, and what I learned, it was very deep pain for a number of them,” Fleming explained. “They said they preferred not to do an interview because it was too painful.”

Also, while the Freedom of Remembrance Project hoped to collect the point of view of those who were teachers and administrators at the time, unfortunately, many had passed away before the project was underway. Despite the challenges they faced, the Louisa County Historical Society managed to accomplish its goal. In the end, 20 former students agreed to share their stories and granted the LCHS permission to interview them for the project, resulting in over ten hours of recorded material.

No two stories shared throughout the interview process were the same. Some of the former students faced challenges with integration but had a relatively decent experience overall. Meanwhile, as indicated by Fleming, others felt traumatized by their experience at Louisa County High School.

“One student vowed never to come to Louisa County again after graduation, and another said they still have nightmares about their time at Louisa County High School,” said Coughlan. While some elements of the oral histories were surprising, the variation between them was not unexpected.

A picture featured in the video “Freedom of Choice: Desegregating Louisa County High School” depicts the first 13 students to integrate into Louisa County High School.

“As with most experiences and memories, the oral histories showcase that every experience was different,” Coughlan explained. “We think of history in a monolithic sense, but really, it’s the cumulative experience of each individual. So, the more voices we speak with, the better an idea of the range of experiences we can have. At the end of the day, the oral histories really bring to light the truly lived experience of history. It’s the commonalities of day-to-day life that bring us together rather than pull us apart.”

Going forward, the society hopes to build on the work they have done so far. “The project, however, is an ongoing endeavor that is still in progress,” Coughlan said. “We still want to interview others who experienced the first years of integration in Louisa County, especially elementary students who were not represented in these initial interviews.”

“I would like to see this story get incorporated into the, say, fourth-grade elementary school history lesson as part of Virginia history,” Fleming added.

Beyond Louisa County, Fleming is extending his expertise and experience from the Freedom of Choice Remembrance Project to develop something similar for Goochland, where he now resides.

In the meantime, Coughlan suggested that people also visit the Smithsonian’s Museum of African American History and Culture to find out more about school desegregation. To learn more about Black history within the state of Virginia, Coughlan said the Virginia Museum of History and Culture and the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia are both great places to visit in Richmond.