50 Years of History at Lake Anna

by Olivia Bridges

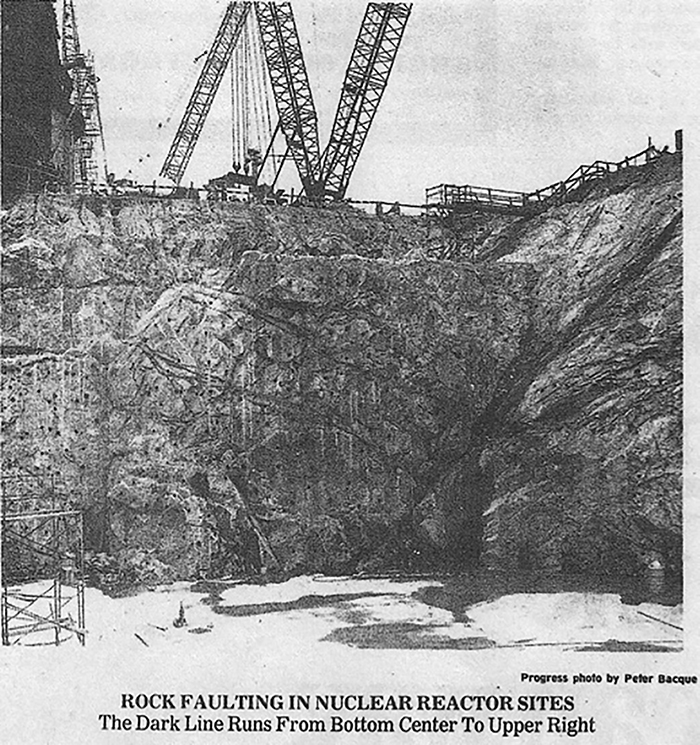

Taken by Peter Bacque in 1973, this historical photo captures the North Anna Power Station as it was being built (photo courtesy of the Louisa County Historical Society).

The Moss family were among those who were displaced due to the construction of the lake (photo originally published in The Daily Progress in 1970, courtesy of the Louisa County Historical Society).

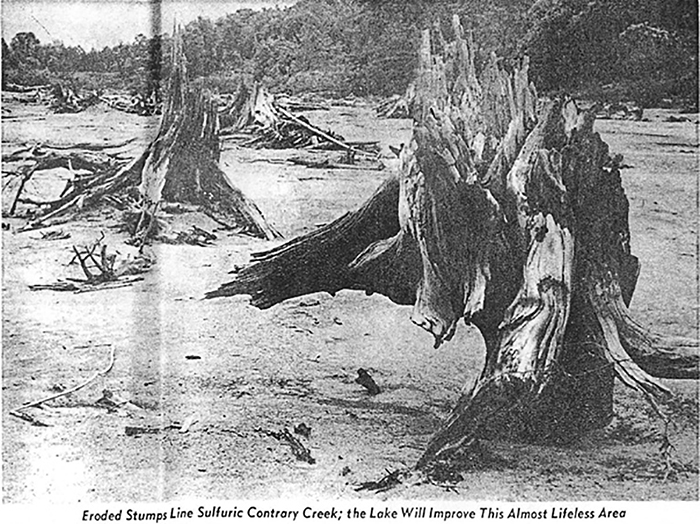

In 1970, an article published in the Times-Dispatch wrote “from an ecology standpoint, [the North Anna River is] actually the worst river in Piedmont Virginia.” The river’s declining conditions were attributed to the north-flowing tributary, Contrary Creek. Fifty years later, a region once described as “an almost lifeless area” is now a prosperous recreational destination due to the creation of Lake Anna.

Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO), which later became Dominion Energy, began a shift to nuclear energy in the 1960s. According to a 1971 summer edition of VEPCO’s magazine, The Vepcovian, the decision to focus on nuclear energy was due to economic factors. While the cost to build the stations was high, the facilities have low fuel costs and yield large amounts of energy.

The first nuclear power plant built by VEPCO began construction in 1968. It is in Surry, Virginia. Also in 1968, VEPCO started purchasing approximately 18,000 acres of land in Louisa, Orange, and Spotsylvania counties to build Surry’s sister station, North Anna Power Station. The company had the right of eminent domain, which allows for the conversion of private land into public use.

The Vepcovian stated that the station would be “the largest nuclear power station in the world when its four units are completed.” However, the company later reduced the number of units to two due to several factors, including cost.

To construct the North Anna station, VEPCO also had to build an artificial lake, otherwise known as Lake Anna, to act as a coolant system. This meant flooding portions of the land the company obtained, including farmland and homes of residents.

“It displaced a lot of different people from multiple counties,” said Katelyn Coughlan, executive director of the Louisa County Historical Society. “I think there’s probably a big degree of people who lived in what is now Lake Anna who have that sense of displacement much in the way that other immigrant communities have, in that they can’t return to because it’s now underwater.”

According to Coughlan, the families who were displaced were generally of African American descent or lower to middle-class white farmers. George O’Connell, a former VEPCO reservoir coordinator who worked at the company from 1973 – a year after the artificial reservoir was filled – until 2010, said that 14 families were displaced. Although, he noted that “they were compensated a fair market value at the time.”

Erosion along the shores of Lake Anna

indicates the need to control this issue

(photo courtesy of Doug Smith).

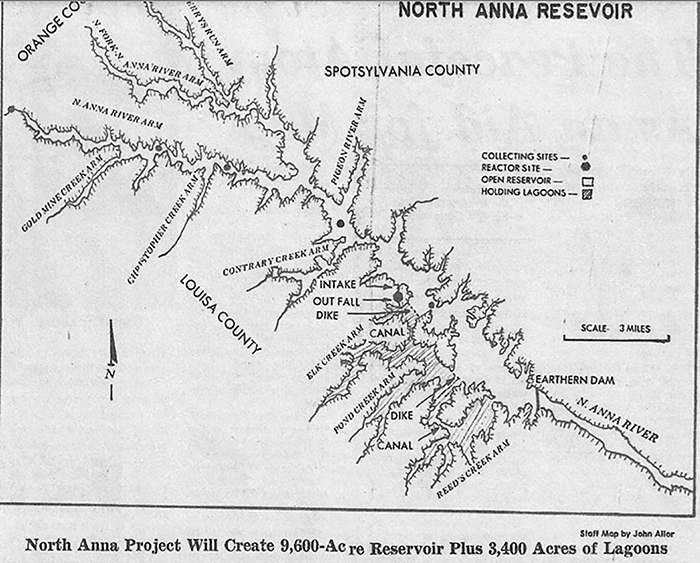

An original map of the plans for the North Anna reservoir

(photo originally published in the Times-Dispatch, courtesy of the

Louisa County Historical Society).

However, others disagree. Jim Marstal, a board member with the Louisa County Historical Society, stated that the Moody and Stubbs families recognized the value of their land. According to Marstal, Moody Town Road and Stubbs Bridge Road are named after the families respectively.

“There was an awful lot of stories going around about the black community being offered prices,” said Marstal. “But they were, in fact, being taken advantage of by the people who were in the know about where the lake was going, and what was most likely going to happen after the lake was existing and in terms of speculation and development, etc.”

Several historical articles indicate that people within the affected areas had mixed reactions to the creation of Lake Anna. Those who were going to be displaced or lose a portion of their land were concerned about their livelihood.

H. Spurgeon Moss fought VEPCO’s condemnation case in 1970. He said to The Daily Progress that because the company planned on flooding a state-maintained road that allowed him access to his house, he should still have a state-maintained road after the fact. At the time of the case, VEPCO offered Moss $11,000 to build a private road.

“If it would cost the state $88,000 to build a road into here, how in the world do they expect me to build one for $11,000?” Moss said to writer Jerry Simpson for the July 26 Sunday morning edition. “They tell us that this lake will enhance nature. But I like nature as it is. With nearly three-quarters of earth covered with water, why do they have to bury all of these farms beneath more water?”

However, unlike Moss and other displaced residents, a 1968 edition of the Richmond News Leader wrote that homeowners and business owners were excited about the prospect of increased recreation and trade.

Earl Dickenson, who ran a lumber business in Spotsylvania, said that the North Anna Power Station was “the best thing that ever happened to this part of the country.”

In 1972, VEPCO finished construction on the dam and began to fill the reservoir, which was projected to take three years with natural rainfall and runoff. However, in June of 1972, Hurricane Agnes significantly progressed the timeline.

Prior to the creation of Lake Anna, Contrary Creek was described as “almost lifeless” (photo originally published in The Daily Progress in 1970, courtesy of the Louisa County Historical Society).

Pictured above is a boating accident on Lake Anna prior to the implementation of certain boat safety measure by the Lake Anna Civic Association (photo courtesy of Doug Smith).

According to O’Connell, despite myths that the hurricane essentially filled the lake overnight, it took until December of 1972 to reach an elevation of 250 feet. A total of 10 and a half months rather than three years.

While there are several other myths about Lake Anna and an overall lack of uniformity in early public opinion, many residents took an interest in the lake’s health and dispelling said myths. Among them is Doug Smith, the retired president of the Lake Anna Civic Association (LACA), formed in 1992 by Jack Bertron.

Smith acted as the association’s president for ten years and served on the board for another four years after retirement. LACA is a volunteer-based organization that prioritizes keeping Lake Anna’s watershed clean and improving recreational activities.

“The Civic Association has been a kind of a voice for the lake,” said Smith. “They’ve done a lot of work, they had a lot of volunteers, and have done a lot of work and used grants and contributions to do the annual fireworks program. And the water quality monitoring program and boating safety programs through the years.”

Shortly after the association’s formation, a hydrilla infestation became an apparent problem in 1993. Hydrilla is considered an aquatic weed and is classified as an invasive species. It first appeared in Lake Anna in 1987.

“It was particularly bad on the warm side and the folks’ docks there; they couldn’t use their dock because the hydrilla had stopped in their dock, and it would foul their prop and foul their water intake,” said Smith.

While LACA attempted to devise a plan to remove the hydrilla and managed to secure $50,000 in appropriated state funds, VEPCO decided to release grass carp to remove the hydrilla on the non-public side. According to Smith, it took two years to clear the hydrilla. However, it later returned in 2015, and rather than VEPCO handing the infestation, the civic association took the lead using the previously-allocated funds.

“It was particularly bad on the warm side and the folks’ docks there; they couldn’t use their dock because the hydrilla had stopped in their dock, and it would foul their prop and foul their water intake,” said Smith.

While LACA attempted to devise a plan to remove the hydrilla and managed to secure $50,000 in appropriated state funds, VEPCO decided to release grass carp to remove the hydrilla on the non-public side. According to Smith, it took two years to clear the hydrilla. However, it later returned in 2015, and rather than VEPCO handing the infestation, the civic association took the lead using the previously-allocated funds.

“The Lake Anna Advisory Committee developed a pilot program to try to manage the hydrilla before it totally infested in the lake,” Smith explained. “And that was with a limited number of grass carp and spot treatment with herbicide, and that controlled them for many years with the use of the spot treatments of herbicide.”

In addition to the hydrilla infestation, LACA also introduced the Lake Anna Special Area Plan in early 2000, which proposed collaboration efforts between the three counties to reduce erosion, improve road access, manage development, and implement water safety measures, including flood prevention. While the plan was not formally adopted, Smith claimed that, “in practice, [Louisa, Orange, and Spotsylvania counties] have really followed a lot of the concepts and recommendations that were in that plan.”

Boat safety is another priority of the committee. They are responsible for putting up signs around Lake Anna, including signs on bridges and docks. This improved safety for recreational boating use, which significantly attracts visitors and businesses to the lake.

“If you have a heart attack on the lake, you know, and you want to call emergency or you have an accident like you want to call emergency, the first thing they’re gonna want to know is where are you, and people had no idea where they were,” said Smith. “And so, we attacked the issue of not being able to know where you are on the lake.”

Lake Anna continues to be a destination for recreational use. Since its creation, it has grown exponentially. O’Connell recalls how the property values have increased over the years.

“Back when I first started working, people were asking for $1,000 for a waterfall plot. Wow. And everybody said, ‘You’ve lost your mind.’ This is $100 an acre of land. I’m not paying you that,” he said. “I could not believe what I was hearing. And I hear it all day long.”

Currently, a house located in the Lake Anna area costs an average of $505,000. However, there are houses that value upwards of several million dollars as a vacation destination. Over 50 years, Lake Anna has also gained name recognition through advertisements and mentions in newspapers. O’Connell said that Lake Anna has exceeded expectations.

“It didn’t happen overnight as one giant success,” he explained. “I think [there is] a lot of enjoyment on the lake itself. I think people have a good time. There’s a lot of businesses, restaurants, and stuff that have come along over the past 20 years that people have and go out and socialize and gather and they’re proud of.”