UVA’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers

by Olivia Bridges

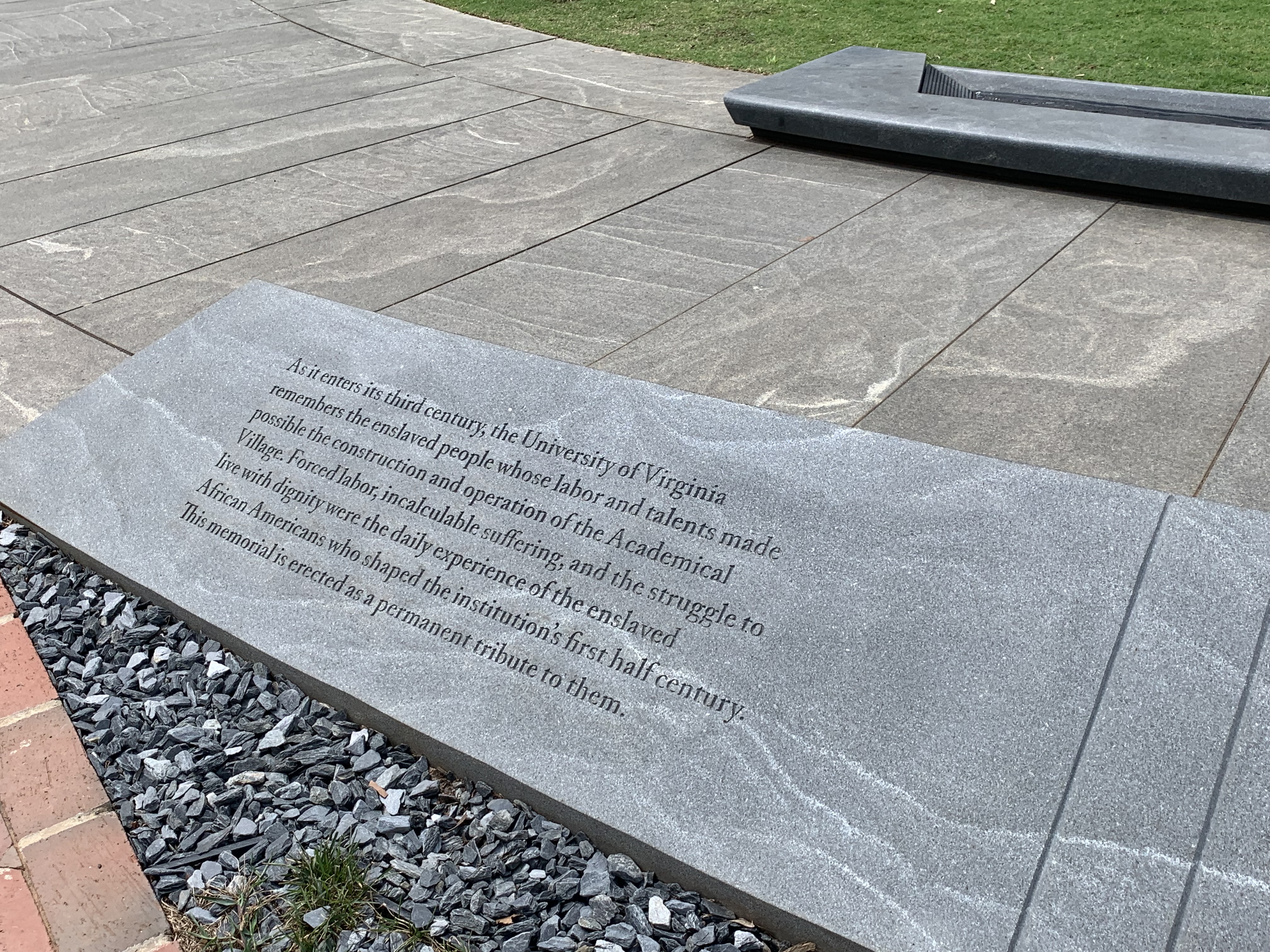

When visitors and students come to the memorial, they can read the inscription of the memorial. It acknowledges UVA’s role in slavery (photo by Olivia Bridges).

The University of Virginia (UVA) began with Thomas Jefferson and an idea that would become the school’s widely revered Jeffersonian Academical Village. The successes of UVA, however, overshadow the fact that the university also began with the labor of ten enslaved people.

Over 200 years after UVA opened, the university’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers publicly recognizes the violence and cruelty that built one of Virginia’s most prestigious public universities.

“Enslaved laborers and freed laborers were inundated at every piece of the grounds at the university,” said Dr. Shelley Viola Murphy, UVA’s descendant project researcher for their Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

Slavery accounted for the majority of the workforce that built and maintained UVA in its early years. Between the start of construction in 1817 and the end of slavery in 1865, it is estimated that the university had at least 4,000 enslaved laborers who lived and worked on its grounds in some capacity.

However, the university did not acknowledge its history with slavery until 2007 when its Enslaved Labor Plaque was installed. In 2010, a small group of students objected to the plaque and led an effort that eventually resulted in the establishment of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers.

The two open circles represent emancipation and the breaking from the shackles of slavery. The memorial is located in a field that enslaved laborers used to work (photo by Olivia Bridges).

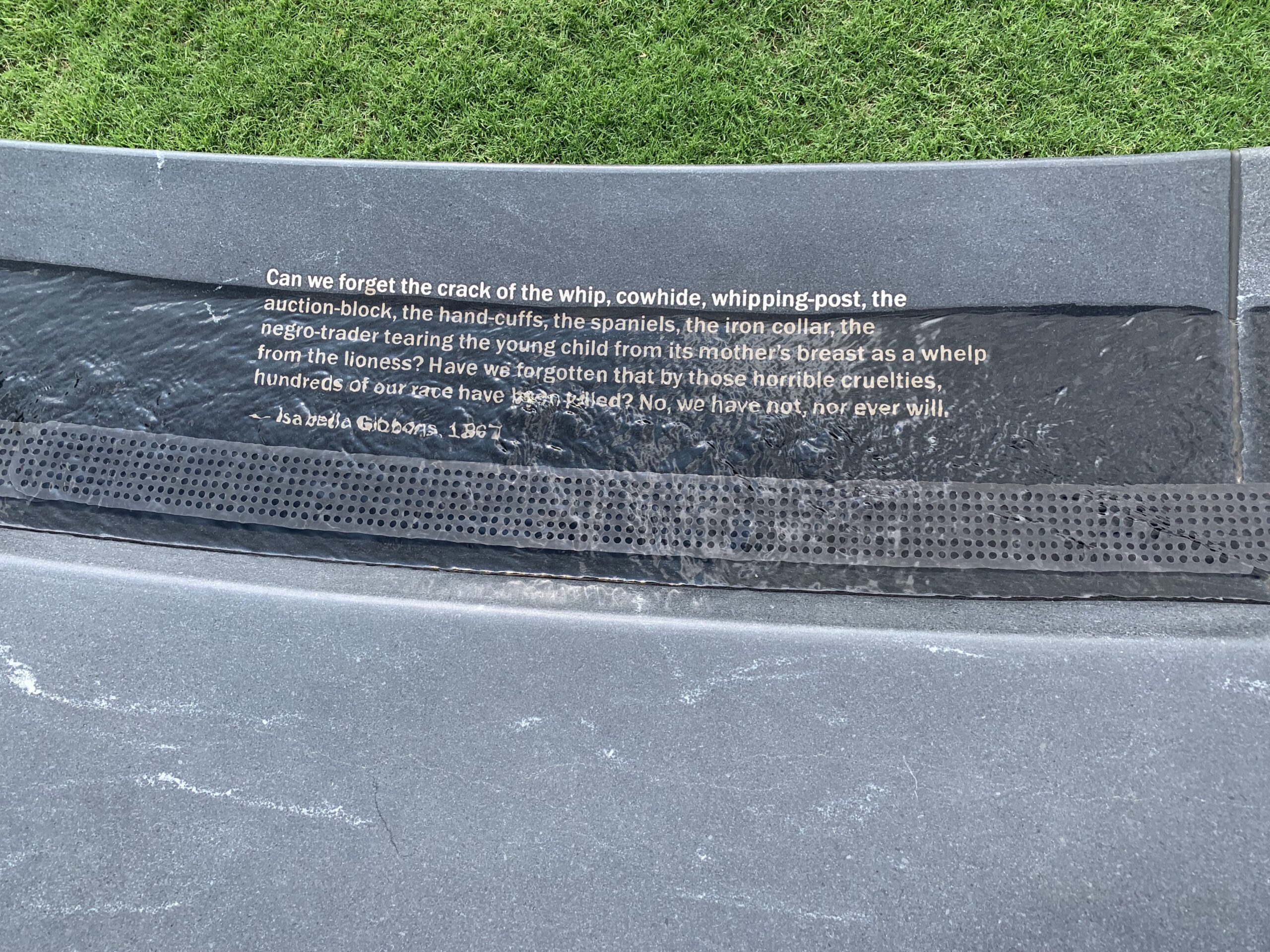

The inner ring features a timeline with a quote from Isabella Gibbons. In the quote, she urges her fellow freed slaves to not forget the horrors of slavery (photo by Olivia Bridges).

“I want the students, the faculty, and the staff to stop and think that 99.9 percent of everything that was built in the United States was built by slaves,” said Cauline Yates, a descendant from the Hughes and Hemings lines of slaves, in a video provided by Murphy.

The memorial is located within the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site, adjacent to University Avenue. The location is publicly displayed and a gesture to the community. It is also the location of a field that enslaved laborers were forced to till to feed students and faculty.

As part of the memorial, the names of enslaved laborers and their descendants are etched into “memory marks” on the eight-foot interior wall of the outer ring of the memorial. The memory marks are intended to address the violence of slavery, likened to a whip.

The eight-foot height of the outer ring was specifically designed to be the same height as the serpentine enclosure Jefferson built to hide the enslaved laborers from students and staff. According to Kirt von Daacke, the co-chair of UVA’s President’s Commission on Slavery, Jefferson designed the university “knowing that enslaved people will be involved in every step of the process.”

According to Murphy, the memorial currently has about 580 names, but there is room for up to 4,000 names. The process to identify the descendants is ongoing and will be a long-term project. Officially, the university only bought and owned one enslaved laborer; the remaining slaves who built the school were rented.

The inner wall of the outer ring features “memory lines” with the names of enslaved laborers and their descendants. Text on the wall also lists the job occupations of the enslaved laborers to recognize the labor the university stole from them. The inner ring has an engraved timeline with flowing water (photo by Olivia Bridges).

“The students were not allowed to bring their enslaved laborers to the grounds, but professors could, so you had a combination of professors who were renting their enslaved laborers as well as local other slaveholders, plantation owners,” said Murphy.

The school’s labor services were recorded on a financial ledger that detailed the amount paid, but the ledger often omitted other important details. Many laborers were only listed by first name and had missing information, like location and the slaveholder’s name.

As a result, Murphy has to either search for descendants based on location or research slaveholding families and their records. She developed a targeted area in Central Virginia around Albemarle County, which includes Louisa County.

“I’m walking through thoughts, research, challenges, successes, whatever is there because slave era research is very difficult,” she said. “I’m not going to say that the work is not challenging; it is very challenging, and it takes a lot of patience.”

Murphy began conducting genealogical research on the memorial in July of 2019. She is the only UVA staff member working on identifying living descendants of enslaved and freed laborers. However, she does receive help from other local genealogists, community members, and historical societies.

Since Murphy has started working on the project, she has identified close to 60 descendants. The true number of descendants identified is likely much higher than this, because the number does not account for the family members of the individual descendant. For example, Murphy recalled one family of 16 descendants that she only counted as one.

The inner wall of the outer ring features “memory lines” with the names of enslaved laborers and their descendants. Text on the wall also lists the job occupations of the enslaved laborers to recognize the labor the university stole from them. The inner ring has an engraved timeline with flowing water (photo by Olivia Bridges).

As a result, Murphy has to either search for descendants based on location or research slaveholding families and their records. She developed a targeted area in Central Virginia around Albemarle County, which includes Louisa County.

“I’m walking through thoughts, research, challenges, successes, whatever is there because slave era research is very difficult,” she said. “I’m not going to say that the work is not challenging; it is very challenging, and it takes a lot of patience.”

Murphy began conducting genealogical research on the memorial in July of 2019. She is the only UVA staff member working on identifying living descendants of enslaved and freed laborers. However, she does receive help from other local genealogists, community members, and historical societies.

Since Murphy has started working on the project, she has identified close to 60 descendants. The true number of descendants identified is likely much higher than this, because the number does not account for the family members of the individual descendant. For example, Murphy recalled one family of 16 descendants that she only counted as one.

Aside from the financial ledger, Murphy relies on the Facebook page “Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA” to find descendants. There, she provides information about how descendants can find their ancestors who were enslaved at UVA.

Those who are possible descendants fill out an intake form that asks for the names and birth locations of their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents.

Murphy also holds one-on-one meetings or group meetings with people who want to know if they have an ancestral connection to UVA. Due to COVID, those meetings are currently held online via Zoom.

Murphy wants both descendants of enslaved laborers to contact her as well as descendants of slaveholders. She is hoping to receive information between 1817 to 1870, because that will provide her with enough data to reach the 1870 census.

“Records and resources are with the slaveholding families and are still in their family collections, and if they are open to sharing, I’m open to receiving that information,” Murphy explained.

In addition to identifying enslaved laborers at UVA, Murphy also wants to debunk myths about African American genealogy.

“One myth is that individuals – African Americans – cannot find their family before 1870, which is not true,” she said. “We are finding our enslaved ancestors daily.”

Murphy wants to make it clear that the “1870 brick wall” myth is just that: a myth. It is possible to track enslaved ancestors before 1870 with the aid of resources like the non-profit “Descendants of Enslaved Communities at UVA,” which is available to anyone seeking information.

“Another myth is that enslaved individuals took their slave owner’s last name or surname, which is not [usually] true,” she said. According to Murphy, only about 15 percent of enslaved laborers took the surname of their slaveholder.

The architecture of the memorial was done in collaboration with UVA, Höweler+Yoon architecture company, and local community members. Each aspect of the memorial intentionally addresses an aspect of UVA’s history with slavery.

The outer circle of the memorial is intended to be a conversation with Jefferson’s design of the Academical Village. The circle is 80 feet in diameter, which is the same size as the rotunda dome. The eyes of Isabella Gibbons, an enslaved woman who lived at the university, are sketched into the outer circle wall. The eyes on the circle come from a photo taken in 1870.

Gibbons went on to be the first teacher of color at the Freedmen’s school after emancipation in 1865. UVA learned about Gibbons from a local community historian who researched her 20 years ago.

Much of the memorial addresses Jefferson’s complacency and desire to hide the realities of slavery. A theme throughout the memorial is to make the invisibility of slavery – and UVA’s history with it – visible.

Gibbons’ eyes play into that message because they can only be seen at certain angles during the day. Often, people will view the memorial without noticing her eyes, highlighting the invisible nature of slavery.

“UVA students, they will care… and then they won’t. Like they are going to walk past it to go to the corner, which is where all the restaurants and the bars [are]. That’s their line of sight; they’re not there to see the memorial,” said Kelsey Chavers, who is a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Charlottesville. The organization was actively involved in the early stages of the project.

“You are around [the memorial] all the time, and like you’re engaging with it, but you’re not fully seeing [the eyes],” she emphasized.

While Gibbons’ eyes may not always be visible to viewers, her words are permanently carved into the inner ring on the timeline with flowing water. The timeline begins in 1619 when there was the first written mention of enslaved Africans in Virginia. It ends in 1889 upon Gibbons’ death.

“Can we forget the crack of the whip, cowhide, whipping-post, the auction-block, the hand-cuffs, the spaniels, the iron collar, the [n-word]-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness? Have we forgotten that by those horrible cruelties, hundreds of our race have been killed? No, we have not, nor ever will,” said Gibbons in 1867, according to the timeline.

The memorial also has an engraved dedication to the enslaved laborers, acknowledging the daily suffering they had to endure to build and maintain the university. The dedication can be found at the opening of the outer ring. The inner ring also has an opening; together they are supposed to represent breaking the shackles of slavery.

“I liked the symbolism of the carvings in the stone, and I also really liked the water,” said Alison Travis – a UVA alum with a psychology, political philosophy, and law major – after viewing the memorial for the first time. “I think a lot of thought went into the design of it, which I really appreciate.”

In addition to the two rings and outer wall, the memorial was designed with an open grass area that mimics a hush harbor or ring shout, which were enslaved community activities that happened at night. It is supposed to be a gathering space for UVA and community members to reflect and protest.

In Murphy’s opinion, as a Black woman, she sees the memorial as a sacred, protected ground where she can go and “either silently protest or be there as a gathering place.”

“I would be proud to stand in there, representing and calling out [enslaved laborers’] names that are on the wall or the names that aren’t on the wall yet that are coming,” she said.

To contact Murphy about any possible family connections you might have to these enslaved laborers or slaveholders, please visit the Facebook page “Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA.”